The Radical Inclusiveness of Advent

On the dining room table in our house, a bundle of sage sits next to the Advent wreath.

Every night we read from our children’s Advent book, and then from Keepers of the Earth, a book of Native American stories written by Michael Caduto and Joseph Bruchac. I turn the Pandora station from Frank Sinatra Holiday Music to Powwow Dance in the middle of the day while I’m doing dishes, because this is what an Indigenous Advent is like.

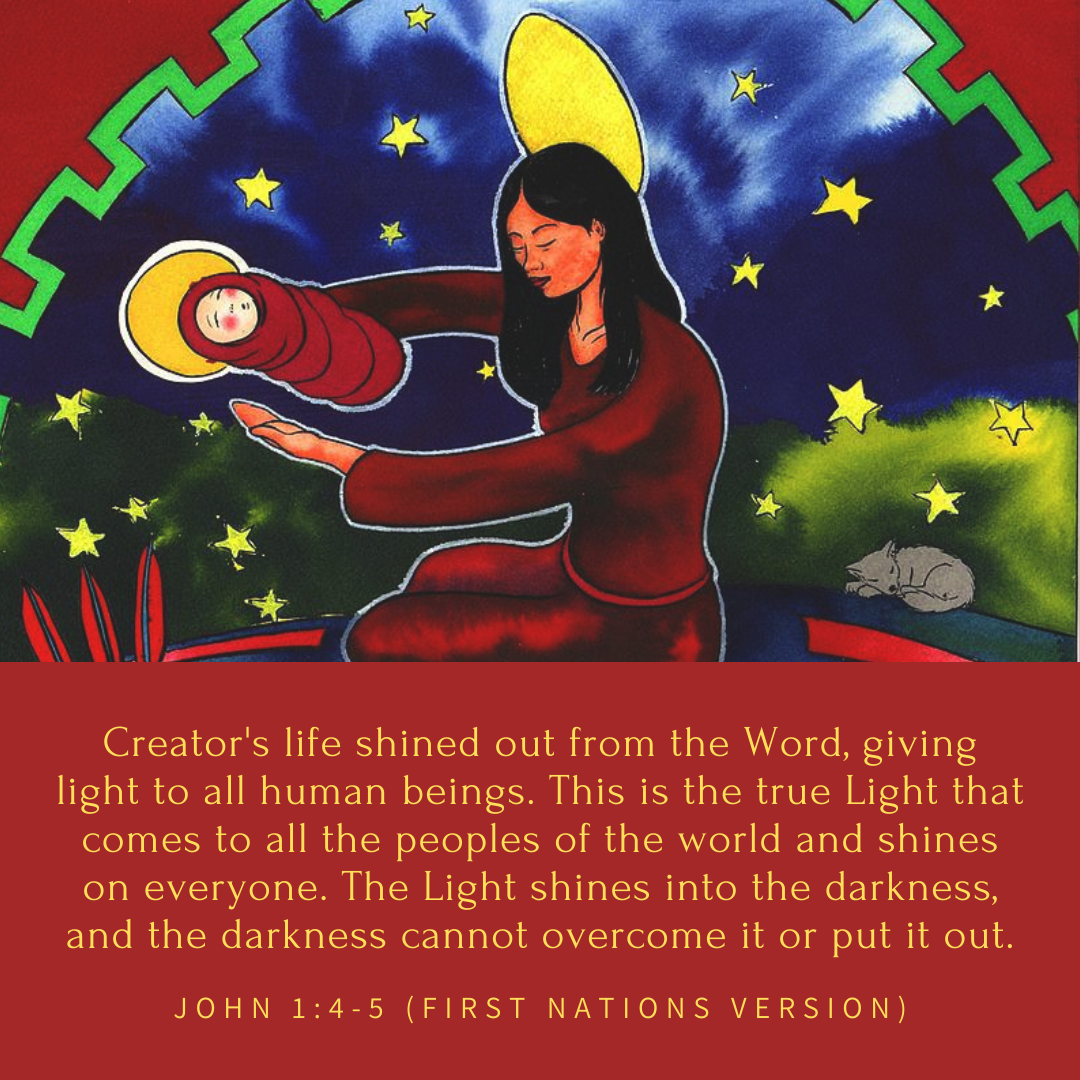

This is the way of walking two worlds with one spirit, one spirit that sees the path of Christ to be the path of native culture, as well.

For native peoples, and specifically for my Potawatomi culture, seeing and experiencing God in this world happens through all the senses, through ceremony, through experience and prayer. In those things, Jesus is always present, the Holy Spirit breathing on us like the wind that blows outside. But it’s difficult for many American Christians to understand that, to grasp that tribes that have been called savages for so long could actually have the presence of God in their own culture’s values and norms, even at Christmas time.

If you look at our consumer Christmas history, you’ll see the tension between the values of indigenous peoples and the values of corporate America. Instead of Advent as a time to be still, to listen and to wait; it’s a time to shop, to stress, to add to the noise. And if you’re not a part of majority American culture, it feels strained and odd to find your place during this season.

But there is a thread within Christianity that calls us back to the silence, to the quiet, to the patient waiting. I find comfort in the writing of Richard Rohr and the ideas of Franciscan theology, which is very similar to Native spirituality. In those spaces of contemplation, care for the Earth and constant work toward being present, we find the true gifts of Advent despite consumerism and colonization.

So, I lean into the frustration and beauty of Advent that allows me to take up space as a Potawatomi woman. Advent allows me to burn sage and pray while I watch the Advent candles burn on my dining room table. Advent allows me to learn the creation story of the Zuni people, to know what it means to see Christ in a culture that has been dismissed by America in every way.

And this year at the Christmas table, I’m adding a wild rice dish, native to the Great Lakes region of America where my tribe originally dwelled. And we’ll talk about it, my husband’s German family and me. We’ll talk about why culture and Advent must go together.

The more I share my experiences of being an indigenous Christian, the more I hear other people say the same—that we are participants in a world we don’t quite belong to—which is the very experience of Jesus, from the day he was born.

So, what does an indigenous Advent give me?

It may just be the thing that shows me how I belong to the good news of the Gospel and not how I’m left out of it.

Maybe it will show me, when I burn that sage and light those candles of joy, hope, love, and peace, that I belong to those who wait, who sit in the tension, who do not always know the way except to ask the created world to show them.

Login To Leave Comment